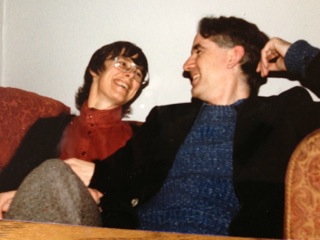

Mum left behind jewellery worth thousands of pounds, yet none of it matters much, not compared to her kitchen apparatuses.

I suppose that's because she rarely dressed up but was a cook seven days a week. The kitchen was a court she reigned with calm authority and industry. Had she been an artist, I'd have rescued her paint pots before her diamond earrings, but she was not. She was a cook and a homemaker - the word "housewife" doesn't do justice to her kind - so it is the tools she employed to run a happy home that pack the greatest emotional punch.

Mum wasn't one for skimping in the kitchen. She was a meticulous and patient cook, one who cut out and kept countless food pages from women's magazines and Sunday supplements besides compiling an index box of her most tried and trusted recipes. A meal was something you took your time over, both in the preparation and the eating (good table manners were mandatory). Granted, Mum always took an interest in technology - she swore by her Kenwood Chef, pressure cooker and electric griddle (essential for making mountains of french toast) - but fundamentally she liked to keep it simple. That way, if the equipment conked out she could follow plan B.

Over the years - my lifetime and more; half a century? - her kitchen drawers and cupboards swelled with utensils and gadgets (one of her last purchases before suffering a paralysing stroke was a Remoska portable oven that my sister Karen would later trot out as a therapeutic aid; it worked wonders). She used every last one of them. How many of us can say that?

Now she is gone, I have inherited a fraction of those devices - a fraction, yet more than enough - alongside sundry pieces of cutlery and glassware. A boxed set of little-used steak knives and forks gifted to my parents on their wedding day in 1963, though my domestic diet is almost entirely meatless. A sturdy nutcracker, though the nuts I prefer come shelled. Nor can I recall the last homemade crepe to pass my lips.

No matter. None of these objects has any monetary value, yet their potency as a catalyst for memories - of my boyhood, of nourishing meals, of my mother (I miss you) - renders them priceless. Therein lies a lesson.