-

For Ian, on Father's Day

Here is an extract remembering my dad, from a longer memoir I've been working on lately, inspired by making The Closer We Get:

Dad trained hard most evenings, changing into shorts and removing his dental plate before ploughing up and down the Largs seafront promenade that connected our house to the town. After an hour or so of grimacing with effort against the onshore wind, his return home would be announced by the front door swinging open heavily. This was one of the few occasions he used the front door, in fact. A gust of wind from the seashore seemed to accompany him, and - as ever with Dad – it was never a quiet entrance. He’d drop down onto to the hall carpet and summon one of us kids out from our homework to sit on his feet as he finished with a few dozen sit-ups. He would tease us, leering over us sweatily, and we laughed hysterically at his toothless grin, feigning to wince at his smell but secretly entranced by his energy, his magnetism, his selfish determination.

He’d then wash for dinner in the downstairs bathroom, using the landing in front of it to dry himself off – he claimed the bathroom was too small for a man used to rugby changing rooms. As this landing was directly opposite the front door, it was all too easy to return home and chance upon him ‘in the skuds’ as nakedness was known in our family – but he was never embarrassed, he just larked about making the towel into a bullfighting cape or a sheik’s headdress until we laughed along with him too.

Dad’s primary parenting tool was humour, in fact, with Mum covering everything else. Unlike most of Mum’s skills, laughter could be hastily deployed – and anywhere. It didn’t need forward-planning, in fact it hated routine. It could not happen without an adoring audience, and Dad’s scarcity at home certainly guaranteed one in his four kids.

I had a prodigious talent for sulking, it was my go-to response to most circumstances that didn’t go my way. And being a third child of four, most things didn’t go my way. When the family had to spend a wet day hiking, I would sulk. When it was banana bread for tea, I would sulk. When Mum bought me a cheapo anorak without asking my opninion first, I would sulk. I orchestrated these sulks with increasing strategy as I got older. It was dangerously easy for nobody to notice you were sulking in our big house, and that was obviously a total waste of time and effort. So I soon learnt it was important to choose the location of the sulk well – clearly it couldn’t take place in the upstairs rooms – such as our bedrooms – as no one went up there unless it was to sleep, and besides, there was no central heating and there was a limit to how much I really wanted to endure for my art. The kitchen rarely worked either, as it was Mum who usually caused the sulk and she was invariably in there – the flouncing out of the room that was the prelude to the sulk was a vital dramatic effect, and you could hardly follow it by returning unannounced just to sit and scowl in the corner. The playroom was an enjoyable place to carry out a sulk, as there were limitless, fun things to do in there meaning I only had to put the sulk back ‘on’ briefly when someone came through the door. The downside of that room was that in fact my parents didn’t often come in there – it was largely and gloriously out of bounds for them – and as it was Mum (and only occasionally Dad) that I wanted to punish with the sulk, there was a real risk that they might never ever find out about the brilliant sulk I had conducted in there all afternoon.If Dad was around, he made it his personal mission to rid me of my precious sulk, however it had arisen. If Mum mentioned my condition to him privately, he would search the house high and low until I was found, perhaps pretending to read a book in the lounge, or if the weather was good, mooching around in the garden, picking up ladybirds or confiding all to the rabbit in her hutch. Dad wouldn’t call out to me, he’d sneak up and then would get down onto his haunches right in front of me. He’d bob his head back and forth but I would not look up, of course. Then came an onslaught of interpretations of the chain of events that – as far as he knew – had caused the telling off from Mum that had spawned the sulk.

“A little bird tells me that a certain person fed her teatime sausage to the dog, and thought she’d get away with this heinous crime....”

“Soooo - you and both of your brothers were in the garden playing football, and somehow your sister Alison pushed herself down the stairs – have I got that right? Well, I guess there’s no need to check the CCTV footage in that case, as you’re so clearly telling the truth”

“What will Mrs Dorman think when she finds out that her star pupil has been sent away to her Auntie Judith’s in Taynuilt, for being such a naughty girl? Well, I expect you might get a Christmas card if you’re lucky enough to be remembered by her and the rest of the class, but Judith only has room for you in the garden shed, you know.”

Each sentence was delivered with a painstakingly dry comic inflection. It was very hard indeed to hold my ground and soon I was unable to resist glancing up at Dad in front of me - fatal. Within a few seconds I was giggling along with him despite my strenuous efforts to remain po-faced.

Triumph would sweep across his face, and standing upright again, he’d say, gently,” C’mon bumblebot” taking my hand and leading me back indoors.

Continue reading -

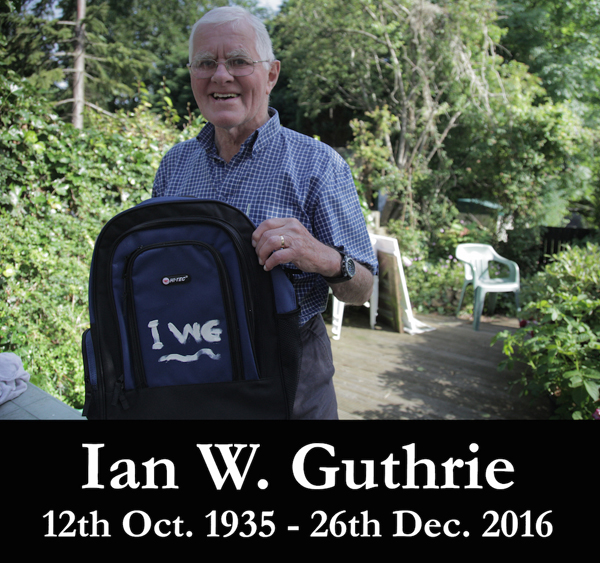

Ian W Guthrie (1935 - 2016): Obituary

We knew some of you will be interested to read this recent obituary (originally published in the Herald Scotland) about one of our main film characters, Ian, who sadly passed away recently.

The death of Ian Guthrie has robbed his family and friends of untold colour and humour, for his was a powerful presence that enriched any occasion, whether a social gathering to mark the birthday of a grandchild or a trip to the pub for a few steadiers and a diatribe about the latest instance of political incompetence, corporate malpractice or sporting controversy.

Continue reading

But Ian would not approve of our indulging in prolonged sadness at his passing. He was an unsentimental man who towards the end of his life gave little impression of harbouring regrets or the sense that his had not been a life lived to the fullest.

Ian William Guthrie was born in Falkirk on October 12, 1935, to Bill, a civil engineer, and Alice, a schoolteacher. He and his younger brother Derek led a nomadic childhood due to their father’s reserved occupation as a civil engineer, spending time during the Second World War in Northern Ireland, where he witnessed first hand the Belfast Blitz of 1941, before moving to Edinburgh and then Glasgow.

Ian was educated mainly at Glasgow Academy where he discovered a passion for rugby which was not only to stay with him until the end of his life but also strip him of his two front teeth. Many years later he would recall having a young Donald Dewar, Scotland’s inaugural first minister, as his “fag” or personal servant, though his assessment of Dewar’s competence as both a politician and a lackey does not bear repeating here.

After leaving school Ian undertook national service as a submariner with the Royal Navy, serving principally on HMS Andrew, an experience he enjoyed to such an extent that he stayed on beyond the mandatory 18 months. As recently as April 2016 Ian fell into hysterics as he recalled an episode involving the overconsumption of beer on shore leave and the consequences within the cramped confines of the submarine.

The next chapter for Ian was an undergraduate degree at Cambridge University’s Emmanuel College. By Ian’s own admission his focus was somewhat lacking on the educational side of his time at university but on the plus side his social and sporting skills flourished. Ian took to rowing as effortlessly as he had to rugby, holding the uppermost position of stroke, and more than 20 years later would thrash the rowing machine in the family home as he got into shape for his latest challenge.

After Cambridge and as the 1950s gave way to the 60s Ian returned to Glasgow, where he began training to become a chartered accountant with Peat Marwick. It was at this time that he was introduced to a young nurse from the Ayrshire coast, Ann Kirkland. Frustratingly, Ann was due to emigrate to Canada with her friend and fellow nurse Jean Dyer, the aim being to advance their careers and have new experiences. Despite Ian’s attempts to dissuade her, Ann duly departed Scotland but was soon doubting her appetite for the life she had dreamed of. Following the exchange of a series of transatlantic love letters the couple were reunited in Scotland and in 1963 were married in Overton Church in West Kilbride.

As part of Ian’s training the couple moved to Bad Soden outside Frankfurt in West Germany, where they made lifelong friends and took full advantage of the proximity to excellent skiing runs. In 1966 they welcomed into the world their first child, Mark, and less than two years later they had a daughter, Alison.

With Ian’s foreign posting complete the family moved back to Scotland in 1969 and chose as their base the town of Largs, which Ian and Ann saw as the ideal place to bring up their children as well as within commuting distance of Glasgow for Ian’s work. A second daughter, Karen, was born in 1970 and another son, Sean, arrived in 1971.

For the ensuing decade or so Ian focused on what he deemed the main priority of a father, providing for his family, while remaining attuned to the importance of keeping active through playing rugby for his beloved Glasgow Accies, golf and most significantly running, culminating in his completion of the Glasgow marathon in 1982 at the age of 47. He would often engage his children as anchors for his feet while he performed sit-ups after an early-morning or evening circuit of the streets and promenade of Largs, the false teeth waiting to be reinserted after a cleansing shower. In line with Ian’s straightforward tastes (black coffee, liquorice allsorts, mince and potatoes, oatcakes) his reward after a Saturday-morning run would be fresh grapefruit, a couple of boiled eggs and a slice or two of toast.

Alongside such virtues as self-reliance and perseverance, Ian saw it as his duty to instil in his children an appetite for sport and outdoor activity. In life, as on the pitch or track, a few scars and sprains were inevitable and it made sense to get used to the fact. His success in this regard was nevertheless slow to manifest itself on occasion. Of his four children with Ann only Sean succumbed to his father’s efforts to introduce them to the appeal of golf. Likewise, although Ian would blithely lead his brood up hills while on holiday in Scotland, the Lake District and Yorkshire, promising the reward of half a Polo mint to those who made the summit, it would be some time before any of his children rediscovered a latent interest in hillwalking.

That said, Ian’s children have all taken to sport and making the most of all that the outdoors has to offer, so their father’s persistence paid off in the end. In the early 1980s, a period in which he served as secretary of the Largs Viking Festival, Ian became disenchanted with accountancy and worked for a spell in life insurance, but the offer of a position as a financial director of a shipping firm in the tiny east African country of Djibouti was too good to pass up, especially with the looming prospect of funding further education for four children.

In 1983 Ian left for Africa and for the next decade returned twice a year, finding his sons and daughters developing as children do. Mark and Sean went to Glasgow University, Alison enrolled at St Andrews University and Karen went to Edinburgh College of Art. In the days before student loans Ian’s salary played a crucial part in seeing his children through their studies.

It was upon Ian’s return to Largs from Djibouti that he revealed to Ann and his children that during his time in Africa he had fallen in love with an Ethiopian woman called Tadalech and they had a son, then aged four, called Campbell, who lived with his mother in the Ethiopian capital of Addis Ababa. Ian also insisted that he wished to remain Ann’s husband while planning for a future for his youngest boy in Scotland and ensuring Tadalech and her extended family were financially secure. During the years that followed – in which Ian and Ann separated and eventually divorced but remained interdependent, and in which Ian strived to establish a sound upbringing for Campbell – Ian never shirked from the complexities to which his choices had led. His decisions were not always universally popular but he stood by them and did what he thought was best.

Around this time Ian and Ann became grandparents, first to Alison’s daughter Zoë then to Alison and Joe’s children Emma, Mia, Adam and Lila. Ann was known to them as Nonna while Ian was Papa, a benevolent figure whose idiosyncratic generosity revealed itself in the form of unpredictable birthday gifts and donations of loose change for the buying of sweets.

Ian never expressed a hankering for retirement and continued to work well into his seventies, looking after the accounts for a haulage firm in east London. Not that he would enjoy the fruits of his labours himself, making the weekly return trip south from Scotland by the cheapest means possible, i.e. the night bus, aided and abetted by a couple of steadiers and a carefully filled hip flask. When Ann became severely disabled following a stroke in 2008, Ian in time assumed a central role in the elaborate system of care she required in her home in Largs, as documented by Karen in her film The Closer We Get.

Ian was a pivotal presence towards the end of Ann’s life, elevating her mood while also ensuring she was comfortable in between visits from her carers. During this time Ian began accompanying the Largs Rangers Supporters Club as the Ibrox side embarked on the process of rebuilding after having been demoted to the lower leagues as punishment for entering liquidation. Earning himself the nickname The General due to being the most senior member of the cadre, Ian found relief from his caring responsibilities through travelling to many of Scotland’s less august football venues to watch Rangers climb through the leagues, though his travels were not without incident. Indeed, having become somewhat over-refreshed he was once left behind by the club bus in Cumbernauld after an away game against Clyde and only made it back to Largs thanks to his sister-in-law Judith Duffield pulling significant local strings.

Having visited Ethiopia regularly since coming back to live in Scotland, Ian returned in 2012 and fulfilled a long-held promise to marry Tadalech. Following Ann’s death Ian moved into sheltered accommodation a few hundred yards from the home of Alison, Joe and their children in Govan. Ian became a de facto member of the household and drew fathomless pleasure from gently winding up the younger children and generally geeing everybody along with endless bon mots and fantastical stories, such as his having been a Harley Street doctor until he was struck off, or having taught Rudolph Nureyev everything he knew. Ian understood life, and the fact you shouldn’t take it all that seriously. He also took full advantage of his return to the city in which he had studied and worked, journeying into the city centre on a weekly basis for a few steadiers in the Press Bar with former colleagues of his son Sean, now a journalist with The Herald. He enjoyed observing if not always approving of the changes that had taken place in the city since he was a boy as well as paying regular visits to Govan library.

Ian’s health began to falter last June when he was diagnosed with jaundice. He recovered but then suffered a couple of strokes which stole from him his excellent verbal dexterity, and his frustration was impossible to overlook. Without conversation, without humour, his quality of life was much diminished.

Each of us will have our own particular memories of Ian, and we should hold them close to our hearts. Whether hectoring the Scotland rugby team on TV from his armchair, lapping up even the briefest spells of sunshine wearing his preferred trouser style of tailored shorts or preparing brandy butter at Christmas, Ian Guthrie was a force of nature.

He will be profoundly missed. Ian is survived by his wife Tadalech, children Mark, Alison, Karen, Sean and Campbell, and grandchildren Zoë, Emma, Mia, Adam and Lila. -

China - the screening, the army, the dumplings....

Very belatedly I have finished a Blog post written during the recent and entirely fabulous iDocs trip to Beijing and beyond - my first trip to China and the film's too - so do take a look at that here if you fancy it.

The obligatory terraselfie

Continue reading -

In Case You Missed This Nice Chap

The wonderful Ged Fitzsimmons captured this equally wonderful feedback right after a screening at Glasgow's Tramway:

What People Say About 'The Closer We Get' from Karen Guthrie on Vimeo.

Continue reading -

The Closer We Get - The Prequel ?

A Very Guthrie Christmas from Karen Guthrie on Vimeo.

Back in August, myself and Alice Powell - the fantastic editor of The Closer We Get - holed up in my home studio once again and spent a gleeful week editing extra scenes together, from material shot for the film, that had reluctantly ended up on the cutting room floor. These scenes ranged from yet more of the poignant wisdom of my mum Ann, to a strangely hilarious drowsy chat between my parents,

'What's that special sauce you have with fish?"

''.......Tartare sauce!"

And a compilation of Jack the Cat's movie highlights (this last still an epic work in progress, sorry Mark, I know it's been a long time coming...).This special festive trailer was also begun back in summer, and we're very pleased to share it with you now.

'Creepy Christmas' was a bit of archive home movie from about 2006, that we'd returned to often during the film edit, but that eventually we'd cut out of TCWG. It was too weird, too funny, too extraordinary to find a place and to stay there. Whenever we tried to cut it in it derailed the scenes around it, and made you want to see more of it. Most documentary shoots have a scene or two like that, that end up out because of their strength, not their weakness. Anyhow, 'Creepy Christmas' had been conjured up during a damp Lake District family Christmas when I had somehow cajoled almost the entire Guthrie clan to collaborate on this short film, the story of which was by the oldest grandchild Zoe, who you will now know as one of the stars of The Closer We Get, though back then, she wouldn't appear on film. It involved a 'Christmas Gem' stolen by my brother Mark (a kind of lonely ogre in make-up, chillingly brilliant) who abducted a niece and had to be told to come to his senses by Dad (Santa, in an appalling paper beard) with such unforgettable lines as "If you want people to love you and give you things, then give me back that ruddy Christmas Gem". Mum's cameo as Mrs Claus revolves around her berating Santa / Dad for eating all the mince pies, and corpsing very badly. It's hardly Pinter...Of course, now I can recognise many things in this sort-of prequel to TCWG: I got most of my family on film, after all. But more importantly, there are subtexts galore played out in these stilted scenes: My dad 's feelings about his son, my parents' irritable co-dependency. Even the fact that Campbell bailed out before he could be filmed.

But being one of the last Christmases before my Mum's stroke also lends the film great poignancy for me. I see a fun-loving, extrovert, mischevious side to my brother Mark that the subsequent years ground down, I remember how my parents could make each other laugh like noone else could, in infectious and uncontrollable fits that had them both in tears. I remember how my whole family could, even after all we'd been through, get on the same page sometimes and be brilliant. Together.

Fast forward to Christmas 2012, the last family Christmas with my mum Ann, an event also featured in this festive trailer. This was my first (and to date, last) go at producing the entire Christmas dinner. It was pretty successful, and fun to do (once), but I was reminded how much my Mum must have grafted to feed us all with such apparent ease. It was, of course, NOT easy, but she made it seem so because she loved us.

Although Dad massacred my beautifully-cooked bird in the carving (see trailer above), he redeemed himself by producing his usual brilliant brandy butter. Noone knows how he manages to get so much alcohol into it, but he does (or rather, I do now, because I filmed it). Yep, I complicated the day rather more than most by also deciding to film it. I'd mooted this with my DoP / Co-producer Nina that she could spend the day with us, and quite naturally her partner vetoed this idea. So I'd ended up juggling the camera, the sound kit and a 9 pound turkey. Let noone say I lack ambition.

Mark had been working nights, so appeared only to eat before passing out again. Campbell was on better form and manfully peeled the chestnuts, a job noone wants to do. Mum was drowsy most of the day until noone could get the joke from my cracker,

"Why would you invite a mushroom to a party?"

From the corner of the room and beneath a paper hat over one eye Mum swiftly piped up,

"Because he's a fun guy"Dad was very patient as I filmed not only the brandy butter technique (classified material, surely) but us watching TV, lolling about on the sofa and generally being Christmassy. It was an especially painful decision to edit this scene out of the final film, when it had been so hard-won. So it's with great pleasure I see it now in the trailer for posterity.

Christmas is a hard time to be without Mum, but seeing her become such a star in her own right through the ever-growing success of The Closer We Get, makes it a bit easier.

Happy Christmas, and the whole team thanks you so much for your support of The Closer We Get.

Continue reading -

Thank you, dear audience

After the success off our week-long run at London's Picturehouse Central, I just want to say right here how much every single person in an audience means to me and the team.

Continue reading

As most of you know, we've diddly squat in the bank when it comes to marketing and advertising, and we rely on your word-of-mouth and all the great reviews which you can read here, to attract our audiences.

I have also had some amazing messages of support privately - these are especially affecting, as so many people have comparable experiences in their families and have struggled to overcome the sometimes painful fallout. Our film offers hope of healing, even if - as reviewer Mark Kermode said - this is an 'unfashionable' message ! -

It's About Time

Some thoughts from director Karen on the passing of two years since the death of her Mum Ann, one of our film's stars:

Two years exactly since Mum's death, and I spend a solitary weekend on the kind of pursuits that filled most of her life - Gardening, baking, sewing, cleaning cupboards, fruit-picking and making jam. She wraps herself around my every task, especially in the kitchen - her natural domain. I hear her chide my disorganised worktop, she slurps the foam from the jam-spoon with relish, checks my jars are clean, worries about the set.

I haven't written down much lately, apart from lists and administrative emails. Lots of them.

But the writing-in-my-head hasn't stopped, though 'The Closer We Get' - where it all went for 4 years - is done and dusted and out in the world now.

And that feels very strange, and rather sad. Where should all those thoughts on grief and bereavement, joy and wonder, go now? In Julian Barnes' fine book, 'Levels of Life' - written in the aftermath of his wife's death - he divides the world absolutely, thus - when we are young, by those who have had sex and those who haven't. And then - usually, though not always, later - into those who have grieved the death of a loved one. And those who haven't. Yet, that is.

Perhaps I am now in Barnes' own farther-flung category - those who have shown the world that grief, for a while.

Both the significant and insignificant things I inherited from Mum are now embedded in my domestic and working landscapes, like a matrix of archaeological finds suspended in insignificant mud. But only I would know them as special - I dry my hands on an old striped towel I rescued from her house as we emptied it, I cook with a packet of cornflour from her cupboard, I swallow a vitamin pill from a bottle she began, use her German stapler on my desk.

Mum shared my passion for plants and gardens. In fact it was our strongest bond in my wayward teenage years when we could barely speak to each other civilly, and yet could happily visit the local garden centre for hours together, a boot-full of plants and a treacle scone in the tearoom to recover from the array of choice. She insisted she lacked expertise as a gardener, and yet she effortlessly grew enormous, slug-free clumps of some of the choicest plants we found together. She always deferred to my tastes when it came to her garden, perhaps regretting it at times. I remember a year or so before she died, she told me, from her wheelchair parked up at the window, 'I really miss that wee patch of lawn we dug up, you know".

For over a year after Mum's death, gardening - which I'd done so habitually since childhood that I wouldn't even call it a 'hobby', to me it was just something I always did a great deal of - meant suddenly very, very little to me. The ebullience of nature felt like an affront, how dare it return? Gradually though, we have found each other again, and I take pleasure in the imaginary chats I have now with Mum as I garden - she'd 'shoot the boots off that cat'who's done its business in the border, and she'd certainly have those goosegogs in the freezer by now.

I find this plant label (pictured above) at regular intervals during my sessions in the garden now, and it always stops me in my tracks. Somehow I don't want to 'save' it indoors, I want it to live the ad-hoc life it should have had, a life of insignificance, not the life of a memorial. In Mum's neat hand-writing - note the 'dashed' number seven, another thing I inherited from her - a sowing of hardy annuals is recorded. I hope they came up, and I hope they were beautiful. Because 2007 would be the last summer before her stroke changed everything. Summer 2008 was spent in hospital, windows jammed shut, garage flowers at the end of the bed. The later ones were spent wheeled out onto the specially-modified deck at home, watching me fight back the ever-increasing wildness of the garden and murmuring appreciatively when I brought tiny cut flowers to her table for her close inspection.

Last summer, we planted a young tree in the churchyard garden in Mum's memory - a spot overlooked by the handsome big house that was our family home for over thirty years. It's not doing well, apparently, so out it must come. Mum would be unsentimental about such a thing. I think we should replace it with one from the garden centre up the road, the place that kept us together all those years ago. "Well, what on earth are you waiting for?!" I can hear Mum say impatiently.

Mum in her garden in 2009, with the trowel I made her at school ! First published in Tales from there Rural Laptop

Continue reading -

An Interview with Karen

A long overdue share of this nice interview I did during Open City Documentary Festival in London last month, which is interspersed with scenes from our trailer.

.

Continue reading -

“I'm supposed to be indestructible”

It occurred to us that some of you may not have read director Karen's writing from before the film was born. For some years, she's occasionally blogged on 'Tales from the Rural Laptop', not just about her family but latterly mainly so - we think some of her posts deserve re-publishing here now, so for starters, here's a Post from 2010, a year before Karen began to film The Closer We Get....

"I'm supposed to be indestructible" are my father’s words down the phone-line, as he recuperates after a mini-stroke he has suffered at work in London. Mum – in hospital again herself for stroke-related bowel problems – speaks to him encouragingly via my mobile phone. She tries to gee him up, they share an innate and now rather comic stoicism despite being ex-husband and wife - albeit the friendliest you could hope for.

Earlier on that day I made use of mum’s hospital stay by having a big and overdue clear out of her kitchen cupboard, a space that had become chaotic without her fastidious and regular attention. As my brother had pointed out a few months ago, this Mary-Poppins-bag of a place still contained the water bowl and collar of our family dog – dead for some twenty years; a rug beater in a house with no rugs; tennis equipment for a garden with no lawn and inexplicable oddities such as a single shelf bracket and meticulously-dated empty lightbulb boxes. Mum was no hoarder – even as a child I was unsettled by her unsentimental attitude to possessions that had passed their sell-by date – so this space was a surprisingly intimate view of the important minutieae of her life before she became ill.

I had to re-assess many useful things within, now with the acceptance that the bicycle clips would not be needed again, that she would never be able to water a houseplant now, nor mend a fuse. I even found the bag she must have used on the very day of her devastating stroke – complete with an array of cloths for her cleaning job, a tiny notebook recording hours worked, and a foil of nicotine-replacement gum.

As I sorted and re-catagorized the last of the neatly packed and labelled objects I found a frail narrative of her feelings on making the move to this house, after seperating from dad and living alone for the first time in her life: a personal alarm, a front-door spyhole and a number of large locks – all still boxed, unused.First published on 'Tales from the Rural Laptop'

Continue reading -

An Anniversary

It's hard to believe that a whole year has passed since we launched the Indiegogo campaign to finish post-production on The Closer We Get!

Looking through my email I see that this time last year I was busy thanking lots of you for your support as we were nearing the end of the campaign and very far from reaching the 15k target! But with your help we got there and I am very proud to say that over 2014 your much-needed funds did exactly what you meant them to: The Closer We Get is finally 'in the can' after a December spent on final sound and music with the talented Doug Haywood and Malcolm Middleton, the latter in the eleventh hour even wrote and recorded a very special new song for our end credits.

Also I need to give a shout out to Kathy Hinde, a talented musician who at the last moment recorded a little accordion music for us…. Our final grading and mixing all took place at Splice.TV in London, and I made sure everyone involved got a wedge of my Ann-recipe gingerbread to say a big thanks :-) My first 2015 job is to get the film trailer done and online for you all, I'm really looking forward to that.

Continue reading -

An Intimate Audience

As some of you will know 'The Closer We Get' is Somewhere's fourth feature length film - and the latest work to come from a collaboration that has now spanned almost 20 years since Karen and I were at art school together in Edinburgh. Until Sunday this week there's still a chance to see the other 3 feature docs. as well as some of our art works new and old. They are all in a retrospective show at Kettle's Yard gallery in Cambridge.

The pieces on show include one of our first projects HOMESPUN made back in 1997 when we spent a week making video/performance pieces 'live' from our parents homes. Karen has used some of this footage to great effect in The Closer We Get - and this was just one of the things she spoke about last Wednesday night during a special talk at the gallery about the development of the film.

It's sometimes a difficult but often amazing experience to watch your own films with an audience but in the case of a film like this - which is SO personal to the director - this is certainly always going to be a challenge. It's one that last week I realised Karen is ready to rise too! She spoke with fantastic clarity about working with her family on the film and the, perhaps, unexpected strength and solace the process had offered to her during extremely emotional and challenging times for them all.

For me it was only the second time to have seen clips from the film with a group of people (aside from Alice, our wonderful editor, and Karen!) and it was reassuring to see both how touching and funny the audience found the material. Of course I think it's a wonderful piece of work and at moments profoundly moving, but having been in the living room for some of the filming, knowing Karen for so long and of course supporting her through the long editing process one can loose clarity on how a fresh audience will see the film. We are so close to finishing the project and it's taken a long time so I think it was a great boost for Karen and indeed me to feel the atmosphere in the room with this intimate audience at Kettle's Yard.

I'm really glad Karen recorded her talk … I was thinking forward to when she will still be talking about the film in years to come and wondering if we will recall the clarity she spoke with on this occasion. I think many people leaving felt like me - lucky to have been there at the 'start' of the journey the film will soon be making from a private family story to a film with a public.

Nina - Co-Producer of The Closer We Get

Continue reading -

A Grand Daughter's Poem

Our star Ann's grand daughter Mia wrote this poem about her 'Nonna' as she called her, in 2009, and it's very cute:

"Her grey and white hair shining in the sun,

The black and white cat, Jack.

Ice cream and waffles for pudding,

All the colourful flowers in the garden and the perfume that beautiful,

The burn outside crashing against the rocks,

Her radio playing loudly in the background,

That's definitely my lovely Nonna"

Continue reading -

A Very Fine Place to Start

One of the greatest challenges of documentary film-making is how and and when to start (and end) the story.

I often describe it as - maybe because of my fine art training - 'Where to drop the picture frame'. Lately - on long drives flicking through radio stations - I've been noticing the kinds of songs that start with a punch, the kinds of songs that waste no time at all in laying their cards on the table:

"Tears of a Clown' (Smokey Robinson), "Take Me Out" (Franz Ferdinand - come to think of it, there are not one but two brilliant songs in that track…), even 'Prince Charming' by Adam & the Ants and The Smiths' mystical 'How Soon is Now?'. All of these tracks start with something that immediately grabs you by the throat, it's a kind of irresistible exhilaration, like falling in love.With film, there's no less pressure than in popular music, to grab your audience in the first minute and to tantalise them with something unexpected and yet indicative of what they can expect from the next 80 or so minutes of their lives, a precious slice of their time on earth that they've (you hope) committed to your film.

So, no pressure then, right?Now, this gets a whole lot harder when you are making an autobiographical piece like The Closer We Get.

After all, I'm still 'in' the life story I'm trying to tell you about - it's not over for me! - and the process of forming the story into the film in itself serves as a kind of self-analysis that brings you back to your earlier life experiences - showing you where the story could have in fact truly 'begun'. So you see, the project is ever widening and it's down to ruthless editorial discipline that anything like a manageable storyline emerges. Or in my case my editor Alice's ruthlessness in controlling the moving target that was the film. But also I got a lot of guidance from the Sources2 workshops I took part in about a quarter way into editing - a group of experienced international film-makers who don't know you one bit and hence have no qualms about highlighting what is relevant to what's on camera and what's not. It's been a particular challenge to distill the 49 years of off-screen relationship that my parents shared into something that serves only to propel their present story forward - the seductive qualities of archive easily fall into cliche - and when I skip through earlier taster sequences we cut for various funders, pitches etc, I'm struck by how much 'before now' material is in there, showing that it takes a while to feel the necessary confidence in the 'right here, right now' scenes, where the silences and banter of a couple who 'never really talked' speak volumes.My opening sequence isn't especially innovative - but the ideas for the sequence in fact came easily once we had stopped trying to intellectually 'set up' the film. We discarded many sequences trying to show 'here's a normal day in the life of….' or 'let's tell you who these people are'. Instead, when I tried to show how it felt to be me then, living that life, it became a simpler and much more spare sequence, integrating material especially filmed for it with shots from much earlier, some of which had the quality of naive specialness that I so often - and so frustratingly - only capture at the very start of projects, when I'm at my least guarded stage of enquiry. We do quickly meet my parents within those first few minutes - and hear the start of my narration - but by this stage we are certain that this is not going to be a film 'about' this elderly couple, it's a lot, lot bigger a subject than that.

More on how we ended the film soon!

Continue reading -

A Year On

What a week this has been for The Closer We Get.

The memory of my Mum Ann, and the film itself will always be inextricably linked and so it seems most fitting that on the week before today - the first anniversary of the day Ann died – we have finished our edit at very long last. In fact, my editor Alice Powell and I were working on the film a year ago when the news came of Mum’s passing away. At the time, friends and family often expressed their shock that I could continue to watch and work with all my filmed material during such a painful time. But it has always been a comfort to me to spend time with Mum on screen, enjoying the best of her, and when she had gone, I knew more keenly than ever that the film had to do this extraordinary woman justice. So, with the expert and sensitive support of Alice, we continued to work away on the project and are very, very proud of the result a year on.For so many - happier – reasons, summer will always be the season that reminds me most of Mum: Because she loved closing the lounge curtains to the sun to watch Wimbledon on TV in midsummer; because her neat figure always looked great in shorts, and because she loved the season’s soft fruit so much she used nicknames for most varieties – ‘goosegogs’, ‘rasps’ etc. Our family labrador was once chastised roundly when she was found greedily sucking ripe raspberries from the canes in the back garden, and to sneak an illicit near-fermented strawberry from Mum’s steeping jam pan in the kitchenette was an annual delight.

Many of Mum’s spells in hospital during her five post-stroke years seemed to coincide with summer, something that struck me as terribly poignant. I seemed to spend many a warm day driving up the A74, amidst legions of holidaying families, their cars laden with suitcases, buckets and spades and roof racks as ours once had been on the regular family outings to the island of Arran. Once I arrived, the hospital tarmac would be giving off a heat-haze and there was always a distant hum of a lawnmower in the grounds. Amidst a ward full of patients snoozing in the heat, I’d find Mum and feed her from a now-warm box of fruit I’d picked at home that morning. She was always hungry in hospital, and she would devour it with relish.

During grief and bereavement I have found comfort in many places and things – in using Mum’s coffee maker during the last few weeks work on the film, in keeping her wedding ring close by me and in recreating her wonderful chocolate cake and gooseberry tart. In Julian Barnes short book, Levels of Life, written in the aftermath of the author being abruptly widowed, quotes his dying wife as trying to comfort him with this reflection on her immanent death:

Continue reading

‘It’s only the Universe doing its thing’

Karen -

On Mother's Day: I am Feeling

I’ve finally watched I Am Breathing, a feature documentary directed by Emma Davie and Morag McKinnon, and it inspired me to write the Blog entry below.

The film documents the last year or so of the life of Neil Platt, a sufferer of Motor Neurone Disease, which also claimed Rose Finn-Kelcey recently, an artist and inspiring former tutor of mine.The film has been on my radar for ages, initially via our mutual connection with the wonderful Scottish Documentary Institute and then latterly because it’s simply been a huge and deserved success story of a film.So why did it take me so long to watch it?In a nutshell – because when you have just lived and filmed an end-of-life story of your own (The Closer We Get) it doesn’t exactly make you hungry for others. Even if you know they will be as life affirming, charming, profound and damned important as I Am Breathing is, you find your appetite veering off to some decidedly escapist film fare instead.But, of course, the grief of bereavement will get you in the end whatever you are watching. A few months ago I went to see the blockbuster Gravity in 3D, in a small local cinema. I had popcorn and Coke in hand, I was expecting to have fun. From almost the first instant, I was shocked to find myself weeping behind my 3D glasses. It doesn’t take a psychotherapist to work out why – a woman, alone, in a dark abyss, trying to fix something she knows probably can’t be fixed.So to endure I Am Breathing was hard for me. I managed to stay dry-eyed until about half way through - not too shabby. Amongst the people around Neil is his mother, an unimaginably brave woman who has survived the death of her husband and now of her son from the same dreadful disease, as well as Neil’s wife and small son.So, it seems timely to publish this text about my mum Ann on Mother’s Day, and to dedicate it to the two mothers Neil Platt left behind.Best wishes, KarenI am FeelingExhausted from digging a large plot in the vegetable garden in early Spring, I lie down, utterly flat on the still compacted ground nearby. How seldom I do this now, when as a teenager I think it was a near-daily occurrence, even in the damp West Coast of Scotland. (If further evidence is sought, see final scene of Gregory’s Girl, filmed up the road from my hometown and featuring kids very like we were).For a spell I gaze upwards into the clouds and the bluest of skies, listlessly tracking the odd bird overhead and feeling the good, cold, dense clods support my body’s form. My breathing slowing, my heaviness reminds me of the body my mother inhabited for those last 5 years, inert bar for her head and neck, and an ever-deteriorating right arm. I remember in the mornings the carers manoeuvring it onto its edges, first one then the other, as solid as clay, a deadweight which must be cleansed and dressed. As the women worked across and along her limbs, my mother’s face held the expression of one who is wondering about a barely perceptible distant sound – the vestigial nerves in her flesh were relaying confused yet tangible sensations she could not quite place. If something was uncomfortable to her, and it often was, she struggled to describe to us how, choosing peculiar words like ‘tight’ and ‘soft’ in an attempt to convey what this new relationship with her body felt like.The sky above me suddenly darkened and sleet began to fall on my face. It felt wonderful. In such moments when the natural world seems at its most electrifyingly complete and beautiful and part of me and of all of us, I always think of my mother and I usually cry. In a photograph of her as a teenager walking on a beach with a dog, it’s evidently cold, windy weather as she wears a big jumper and a headscarf. But her legs and feet are bare and her face beams with the sensual joy and fun of cold sand and spray. Until her stroke she retained this appetite for earthy pleasures - eating crusty bread, cycling into the wind along the seafront, stroking a supine, sun-warmed cat.So as I blink in the tumbling sleet, my tears find their path of least resistance from the outer corners of my eyes, down my temples and into my hair, their dampness instantly provoking shivering. I don’t wipe them. Mum very seldom wept after her stroke, it was a very grave sign if she did, but when it happened she could not wipe them, could not lift her hand, and so if I was there I would oblige. But what of the times – there must have been some –when I was not there?After the stroke, Mum’s short spell in physiotherapy ended with a tacit acceptance that this once sprightly woman, the kind of woman that rarely sat down for long, would be wheelchair bound for the rest of her life. Her damaged eyesight meant a self-drive chair would be impossible. Along with the myriad other dependencies (personal care, feeding, medication, dressing) she was also, suddenly and forever, unable to autonomously decide where she would be and when. After a few months of our caring routine kicking in, I began noticing how listless Mum could become with the clockwork carers visits, the porridge and lukewarm tea, the endless daytime television in the over warm lounge. Her bright blue eyes literally clouded over for days at a time.What brought back her sparkle was always something unexpected and invariably something sensory, so I became adept at inventing and stage-managing as many of these as I could fit in to her waking hours, and sometimes also into the hours where she was meant to be sleeping but often wasn’t: Whether it was sharing a fruity face-pack or a blast of loud music with our terrible vocal accompaniment, feeding her a very ripe mango or a very salty chip, manoeuvring a furry cuddle from the longsuffering cat Jack, a cold skoosh of Rive Gauche on her neck, an illicit chocolate eaten in bed or a noseful of fragrant sweet peas.Occasionally these energising episodes also happened without so much pre-planning by me: Shortly after Mum had been returned home from the hospital, we decided to pay a visit an old friend of hers, now residing in a large old peoples home along the coast road. At this stage I’d not yet got used to the fandango of getting Mum into her coat, hat and gloves whilst she was already seated in her wheelchair. But she was patient and after about twenty minutes manipulating awkward limbs and digits and with me in a light sweat by now, I had swaddled her from head to toe and we careered our way out of the house and the close and onto the deserted street. I should have recognised what the peculiar soundlessness and pallor of the day foretold, but keen to reach the beachside ‘Prom’ which had been a daily landmark of her entire adult life I pushed the chair onwards at speed, Mum occasionally complaining good-naturedly over the potholes encountered en route.

Doris, our hostess, was a big, robust woman some ten years older than Mum and suffering from dementia. In her small, neat room, I loosened Mum’s layers and listened in to their conversation, smiling benignly. Doris was convinced that Mum and her had been Wrens in the War together, and no matter how often Mum reminded her of their actual relationship – Mum had been an occasional cleaner and housekeeper for Doris – Doris’ mind would wander off to those wartime escapades she was certain they’d shared. Occasionally Doris would turn to me and speak as if Mum wasn’t there – “She was a gifted telephone operator, you know’. I could not help reflecting on the odd couple they seemed – each with infirmities at such odds with what remained.What if Mum had that fit and strong body of Doris’, and Doris could adopt the alert and perceptive mind Mum still had?We left Doris in time to speed back along the Prom in time for the carers’ mid afternoon home visit, and almost as soon as we were parallel to the pewter gray sea the sky whitened dramatically. A blizzard began and within minutes enveloped us to a dramatic degree – we could barely see 5 metres ahead. By now I was almost running behind the wheelchair, terrified that Mum would be scared and confused, or at the very least rather cross with me for getting us into this mess. Bellowing over the chair handles, I assured her we’d be home in no time, who on earth would have guessed this snow was on its way, etc etc. Snow clung to our every surface, it wasn’t so much falling as propelling itself horizontally onto us. Every hundred metres or so I stopped the chair, dashed round to the front and readjusted Mum’s hat, scarf and collar so that barely her nose and eyes were open to the elements. With every pit stop she was giggling more, until be the end of the journey we were both howling with laughter.When we finally reached home the carers were already indoors, more than mildly concerned as to our whereabouts given the extreme weather. They gently scolded me for being caught out in that with Mum, but as they removed her layers and the fast melting snowflakes we caught each other’s eye and shared a deeply conspiratorial smile.Continue reading